The biggest blessing we have is the figure-out-ability of the universe. Things happen according to patterns and rules, and those patterns and rules are discoverable. And if we figure out the core patterns, they are fairly consistent and allow us predictability over at-least a short span of time. Had there been no rules, no patterns, if everything was random, we would have been doomed. There is no such thing as randomness, but only probability distributions.

Category: Notes

-

-

I was wrong about emails

Earlier I had posted on my weblog about why I liked emails as a form of communication. I was so wrong.

Emails are useful form only if the communication is: (i) pre-structured, and (ii) necessitates long-form text. In all other scenarios, you’re better off texting.

The point of conversation is not just to share maximum context, but firstly to find the right shared context, and that requires a very fast feedback loop. This fast feedback loop is not possible in any way other than texting (apart from verbal conversation). Now that I have gotten used to texting, emails feel pathetically slow.

For maximum context dumping and fetching, blogs, essays and books are the way to go.

-

Invent

We can always source ideas for interesting games from other people. Games we see on tv, read about in books, so on and so forth. But somehow, the games that turned out to be most interesting were the ones we had invented ourselves.

This can be generalized to a lot of things in life.

-

Memories

While reading an essay, I notice this. Relevant to something in the essay, I recall a similar experience I had also had. But then I notice this. I had mentioned this experience in an email to someone. Writing that thought had created an indexed entry in my brain. Had I not typed that out, my brain could not have indexed that.

Our memories are very quick to fade. When we write them down, we create a hard impression. But once we do that, our brain says — hah, this fool finally wrote it down somewhere, now I can let that memory go. And it goes and archive that memory into the deeper much hard-to-access archives. With that, the memory of that experience is no longer accessible, and a summarized carbon copy of the impression we had made replaces it.

This idea is frightening. Frightening because we are at the mercy of the accuracy of our impressions. This increases up the responsibility for how we write. It’s way more often than not that people retro-fit a narrative or a vision to their story. But we should aim for impartiality. Because if we have made any progress, it is by realizing the susceptibility of us getting fooled by no other but ourselves.

-

Self-Referentially Ideal Premise

One of the characteristic of a specific kind of faulty premises is that it self-references itself as the ideal premise. (The problem with such logic if not apparent can be seen through Godel’s incompleteness theorem.) The result of such characteristic is that it indirectly mandates that the objective function of a person believing such premise is to spread it as much as he can. But there’s a counter-intuitive consequence of such an objective function. Imagine a few people living on an isolated island hold such a thing and ultimately succeed in selling that idea into the minds of all people in such an island. Now, what are those people supposed to do then? What should be their objective function now that the premise has spread as much as it could be? Well, you can say they also had their own personal objective functions before, why can’t they have again. That is because the premise restricted from them, because it mandated a different objective function — the spread of itself — which ultimately has ceased to be further achievable. If the island is not isolated, then ultimately the people would go out for conquests (which history tells us people usually went to). And the premise would continue to live. But ultimately, the earth is a spheroid — an isolated island in the sea of cosmos. And thus an isolated island is perfectly suitable scale to think why is there no such island where all people are completely sold to such a faulty premise and aren’t living the ideal life as does the “ideal” premise promises them? Because such a self-referentially-ideal premise is like a virus that lives as long as the population of hosts is somewhat immune to it. If the whole population of hosts contracts a fatal virus, it’s not just the death of the population of hosts but also the population of virus itself. That is why there are so many premises mandating the ideal world but not even a single tiny island that represents anything as such. Ironically, if there are any islands remotely resembling an ideal state, they are the kind where people would get horror at even the idea of such an “ideal” premise.

-

Thought Rubberducking

The amount of times I have written something in an AI chatbot’s input field and not pressed enter, and, the proportion of questions I note down to ask to the ones I struck out, because I understand the point already, point out that the rubberducking effects of thinking-in-writing are much underrated, even among people who are somewhat used to writing.

-

Memorizing whole sentences instead of words

There’s this problem with repeating a certain reference work (even with word-by-word translation) on repeat in attempt to learn language. That is, your brain start memorizing whole sentences and their meanings instead of forming individual word by word associations. Even though, one might be able to fully understand the readings on which the language learner has done his exercise, he might not be able to extrapolate that learning, even to another passage that uses the very same vocabulary. Language learner should thus be wary of this illusion and constantly stream himself newer stuff (even though containing same level vocabulary).

-

Chair

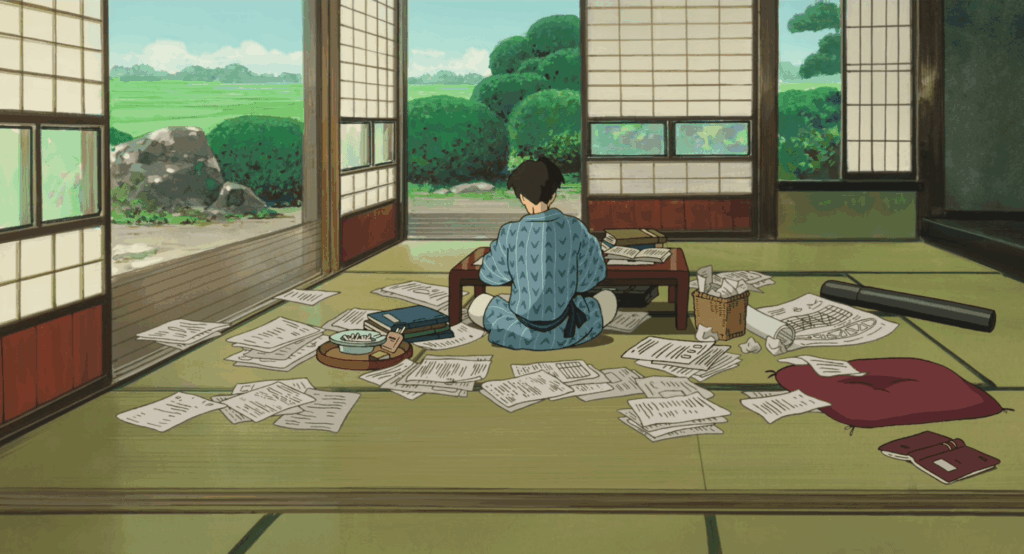

A chair is an enclosing structure. A low-height table with which you are supposed to sit on ground is better than an elevated table and a chair, because on ground, your body is not enclosed in a structure and hence enjoys greater deal of flexibility while moving around.

Example of a good work setup

-

Learning

Learning is not acquiring of information. Learning is an act of discovery. Perceptive observations and skeptical inquiry are what drive this act. A teacher is a person who trains a disciple to become better at observations and more thorough in his in inquiry.

A student’s discovery is distinct from his teacher’s discovery. Teacher’s own discovery is no substitute for his student’s. And a student’s discovery needs not to be less insightful than teacher’s own. The student-teacher relationship is asymmetric in time but not in value. Both benefit from each other’s discovery.

Books are not a store of information to be acquired. Books are field-diaries of people involved in act of discovery, and hence a highly useful resource for one’s own acts of discovery.

-

When asking question, also show your thinking

I just read this:

https://talhaashraf.com/showThis principle is applicable and also useful when you are asking someone a question. You can show them your thinking process that leads to the question. This gives them the relevant context for why you are asking the question, how’s that relevant for you, what parts you’ve been able to figure out and what parts you got stuck at, what you’ve got right and you haven’t, and so on.

If you don’t give your thinking to the person you’re asking a question from, you are basically delegating the task of extracting the relevant context around the question to them, which is not only too much of an ask (and hence rude), but also very inefficient and slow.

There’s exception to this principle though. You don’t need to do this when you are asking someone questions to learn more about them (instead of asking question about a specific matter or a problem). In this case, you should rather try to make your thinking less visible. Because people often subconsciously adapt their responses according to their perceptions of the inquirer’s desired response. And even if their responses are not modified and representative of their true self, they will still be restrictive to narrow specifics. When you want to learn about someone, you should rather question them in a way that allows them to be more explorative about themselves so that its beneficial for both of you.