oldest to newest (change)

-

The Hard Questions

At every point in human evolution, accepting some form of discomfort was essential to the long term survival of the human species. Who was it, I can recall recently reading or listening to someone saying imagine if our ancestors had gotten so wonderstruck at a flower or something spending hours just looking at beautiful stuff that they hadn’t gone hunting or might have gotten hunted. Going hunting was uncomfortable, but we did and survived.

I believe, it also sort of got ingrained in our mind, that we think if we are experiencing some sort of discomfort, we are doing something right, which essentially not needs to be the case. It can be anything.

But I think what of it remains relevant today is about asking yourself some hard questions. It is very uncomfortable, but it’s essential. It’s very easy and all the more tempting in this age, to not really stop yourself and ask, why are you really doing that? What is it that you believe in? What is it that you stand for? Does it all matter? What matters and what doesn’t? On what premises are we going to decide that? What’s really going on?

Historically, what we did was to not think about them but go looking for someone who’d tell us the answers. Since we didn’t do the thinking, we didn’t know whether they were right or wrong. What we do now, is to just shrug these answers away. Just like that. Without even asking anybody.

There is a cost to both kinds of laziness – physical and mental. And we can’t get away with either of them. That is, if we want to survive.

-

Default

Most people run on defaults.

In computer or mobile, there are a lot of settings you can tinker with, so that you can get from your device what you want out of it. When you get a new device or install a new Operating System, there are settings that are already set there. Such settings are called the device’s defaults.

Just like there are device’s defaults, there are life’s defaults. Let us derive some points from the analogy.

The reason there is an option to tinker with settings, is so that the user of device can make the device fit them. However, most people do not go tinker with the settings UNTILL they encounter a problem that bugs them a lot. Only then will they look on how to fix that specific problem or ask a geeky person to fix it.

The point to notice, is that the user will have the device’s settings tinkered only for things that bugs him a lot. But there would be a dozen other options in the settings that also could have made that person’s experience with his device significantly better, but he didn’t even know about them, and hence he did not change them. [Post under editing]

——–

He didn’t know that he shouldn’t think of devices as given, he should think of them as invented, something made, something designed, by someone. The devices are a product of someone’s intention of making them. The particular way that device behaves is because someone decided to make it behave that way. If the device works that is because someone did put intention into it1.

But the point here is not merely that everything you see is a product of someone’s intention, but it is that someone else’s intention can’t make things any better for you beyond a limited extent. The ideal thing human beings can do for others is to make things with better defaults and providing a way to change them, but they can’t make things work for you, unless you put your own intention into making something work for you, and unless you make your own decision of what you want to get out of that thing.

So, default2 is the situation that exists without the intention of the person to whom that situation concerns. And when there is no intention involved of the person about any particular thing that concerns them, that particular thing usually does not fit them. In this essay I’m not worried about the defaults of the devices people use, but about the defaults of lives that people live.

Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing.

—John Stuart Mill

The idea of having a life that fits you is very well described by Henrik Karlsson in his essay titled Everything that turned out well in my life followed the same design process, that you should read further to understand that aspect. An excerpt:

“Eventually, I looked up and noticed that my life was nothing like I imagined it would be. But it fit me.”

“When you design something, a useful definition of success is precisely that—the form fits the context—as Christopher Alexander argued in Notes on a Synthesis of Form (1964). This is true of relationships, and essays, and careers: you want to find something that fits.

- A glove is well-designed if it fits the hand nicely.

- A relationship is healthy if it fits the personalities and needs of the people involved (and the resonance between them).

- An essay is good if it fits a context made up of 1) the truth, 2) the intellectual needs of the writer, and 3) the reader’s mind. The better the form fits that context—the truer, more insight-generating, and resonant it is—the better the essay.”

And so when I say, most people run on defaults, that means they do not put intention into what they do, and hence let different aspects of their lives to develop in a way that does not fit them. And when they don’t intentionally work to develop their lives a form that fits their inner context, they are essentially trimming their their inner context by forcing it to fit whatever form is developed by defaults.

Many people run their lives on default3 and a telltale sign is that such people seem to have problems in some important aspect of their lives that are solvable (and still remain unsolved)—problems that do not involve any real tradeoff, or, opportunity cost, except, for the effort one has to put into resisting the inertia of defaults.

So, that is the problem of default. The way we solve this problem is by keep asking ourselves questions (about why we are doing things we are doing, and the things we ought to be doing, why we are doing them in the certain way we are doing them), and by deciding to do whatever we do with intention, and then using that intention to work on developing a life that fits.

https://www.henrikkarlsson.xyz/p/unfolding

- Sometimes, devices do come out even with not much intention put into them. These are what make up the crappy devices. ↩︎

- As the word default is very common for device settings (or device behavior), the closest word to that for human behavior is norms. But when people think of norms, they usually think of culture…, and religion…, and, our beliefs…, and grand and abstract things like that. Of course, these things are sources for defaults, but it is a very limited view of the defaults for humans, because there is a whole lot of things that you wouldn’t think of, when you’d think of culture or religion or social norms, etc., that too are defaults. ↩︎

- The thing about defaults is that they are not so easily noticeable because the defaults in different social-circles vary, just like the defaults of different operating systems vary. People might even look down on defaults of another circle while themselves running on defaults, just different ones. And this makes it tricky because some defaults are apparently better than others. There was a certain period in my university-time, when I used to think that the things are so better in certain private universities (as I was in a very inexpensive and unfancy public university), students there take much more interest in learning different things and doing different things, and so on. Only after observing and interacting with students and graduates of those institutions for some time, I came to realize that earlier I wasn’t looking closely, and hence missing a very important about people at these places. It was that they belonged to a place with different (and apparently better) defaults, but they too were running on defaults, and NOT doing whatever apparently interesting things they were doing, with intention.

Defaults do not necessarily mean stasis, and just because someone is not static and constantly doing something, does not mean they are not running on defaults. The defaults are like inertia of an object in motion. Or like streams with heavy flow of water. Different places have different streams (or defaults) running in different directions, with different speed. And the thing to do, is not to jump from one stream to another, or to try to swim upstream, but to get out of the stream. ↩︎

-

Gall’s Law and Feedback Loop

Few days back, someone I follow on Curius had added link of this video on their Curius profile:

This reminded me of the principle described by John Gall:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system.1

If you think about it, you see it everywhere, from evolution of life, to all the technological progress, to the idea behind MVP.

But the thing is that we live in times where technology has gotten so sophisticated that it is becoming harder and harder for us to imagine about simpler technology that works.

Feynman had narrated an example of it about how when he was a kid, they used to open up radios and you could see all the component parts. Basically, when you opened up devices at that time, what you got was a diagram of how that thing worked, but as technology evolved further, it became more and more opaque, and you no longer got that diagram when you opened something up.

But the underlying working principles haven’t changed much. We probably have uncovered more of physics in last 50 years. But the kind of physics needed to build or understand most of elementary things, is not really new; only its implementations have become more sophisticated.

And I don’t intend to say that that sophistication is inherently bad. The technology was bound to get more sophisticated. There was no other way. What I am pointing out is that from the technologies we see around us, we now have a longer route to re-trace to get back to first principles.

Similarly, we look at computer systems and software, and it’s so daunting. Like, just look at the graphics of any modern video game. And it seems unimaginable how humans can program something like that. But that’s because we have forgotten that we once used to play Prince of Persia, Mario, Pac-Man, Tetris and the like.

We look at people accomplished in certain areas, say, for example, writers, and think the same. And fail to realize that it’s not like a person, one day, randomly decides to write something, and comes up with something like Macbeth2. I’m not saying that one can’t one day randomly decide to do something he hasn’t done before and still come up with good results. I think quite the opposite: if someone’s the right kind of person for the job, he is highly likely to come up with good results in his early attempts, provided that he starts with a simple version. A writer doesn’t need to come up with a very sophisticated insight, or a scientist a complicated discovery, or an engineer with a complex invention, in early iterations, he only needs to come up with something that works3.

Now, this seems to be gravitating to very cliché ideas, and so let me turn this around.

Even though all complex systems that work evolve from simpler systems that also worked, starting from a simple system that works, does not guarantee in itself that it will also evolve into a complex system or that it will continue working if it evolves.

What makes a simple system evolve into a complex system that still keeps working is a strong feedback loop.

Those systems that don’t have a very strong feedback loop to guide their evolution, will either have to slow down (stop evolving) if they have to stay working, or will fail at some point if they keep iterating further on whims without any feedback loop to guide them.

A strong feedback loop is one that is strong and both of its ends, i.e., it is (i) highly perceptive at the sensory end, and (ii) it’s highly precise and moderately4 fast in it’s execution.

I think systems get more and more risk averse as they increase in complexity, and that is why most of them stop evolving, and hence we end up at local maxima, never seeing the light of what a global maximum looks like.

- This is popularly known as Gall’s law.

Source: John Gall (1975) Systemantics: How Systems Really Work and How They Fail p. 71 ↩︎ - I haven’t read Macbeth and don’t really know what’s so great about it, and thus, I shouldn’t probably use this example, but I can’t think of any for now, so I am just assuming that if mathematicians use a literary work as an example benchmark in their theories, it must be good enough. ↩︎

- I had earlier written “come up with something useful” but the usefulness is context-dependent and the term works in itself contains the context. For instance, if someone is writing something funny to amuse someone, and it actually amuses them, then it works whether or not anyone thinks it useful. ↩︎

- I say moderately fast because there seems to be a tradeoff between preciseness and speed of execution. ↩︎

- This is popularly known as Gall’s law.

-

Wordless Thinking

Henrik had posted a new essay (When is it better to think without words?) some days ago and I had been holding out reading it. I think I do this because Henrik’s essays feel too sacred to be read casually. And it turned out right. I literally jumped off my feet–several times–as I read it today at dawn.

What makes Henrik’s essays so lovely is that it’s like, there’s a sort of hum of a melody you had heard somewhere in childhood and the details of it are faded (perhaps you had only heard it from far off and your ears didn’t had capacity to perceive those details in the first place), and that faded hum stays in your mind for days and months and years, and then someday, you turn your attention to someone, and they start playing that precise melody that has been taking up your mind for so long, with such sharp and crisp details that your ears start savoring with great attention so as to fill in those missing details, and as the melody is about to end, you are startled as you realize there is more to that melody that you hadn’t heard of before, and what you had been repeating was merely a segment of an extended symphony.

I think I have been doing this thinking-without-words thing, for a few years, even though much rudimentary compared to Hadamard’s. This description seems oddly familiar:

He also saw something that looked like equations, but as if seen from a distance, without glasses on: he was unable to make out what they said.

this type of deep, consciously-blurry concentration

Often when, reading something or paying attention to something for long, excites my mind too much, I go for a walk, that sometimes continues for an hour or more, in which I think without words1. And I feel this strange tension, because there’s this wide panorama, really really wide, and I can see these bizarre connections between remote things, but when I try to zoom in or to look clearly into the details of that thing to be able to validate if that apparent connection makes any sense or not, the whole image shatters and falls apart. And so I am left empty-handed, retaining neither that wide panorama, nor any conclusions about validity of any particular connection/pattern. It’s a very unsettling feeling.

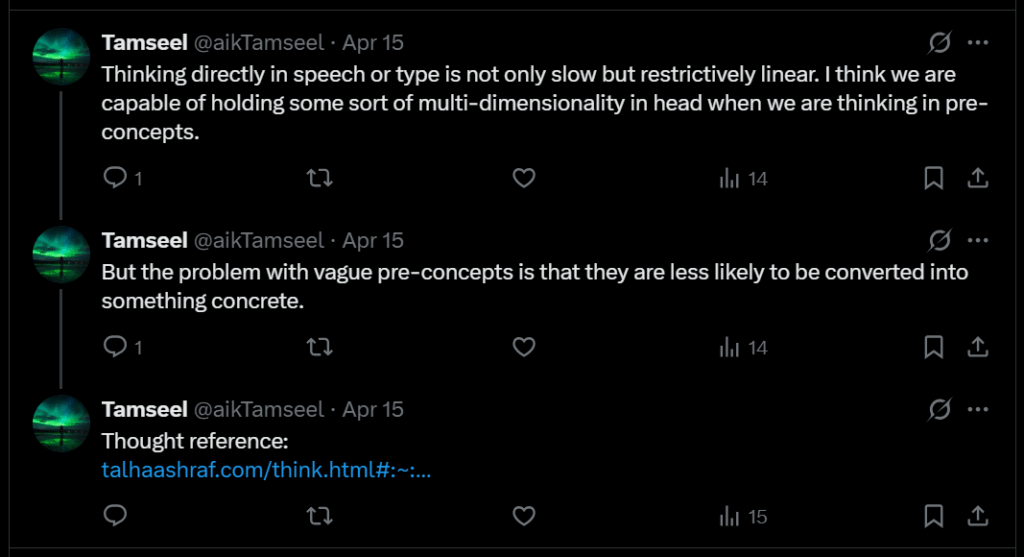

This was how I had described that feeling a while ago:

You can replace “thinking in pre-concepts” with “thinking without words“

The thought reference was the essay Think by Talha Ashraf:

[Deep thinking] depends on not only one level away from direct results but then another level away where you think about the effects of the effects and then again the effects of those effects and then also try to think about the results of these combinations. The only problem with this is that these levels exist as preconcepts, things that cannot even be defined with words because they are too vague at that point. Most of them you probably cant even identify as concepts so you wont be able to write them down and if you cant write them down you run into a very basic problem that everytime you start thinking about them you have to start from scratch. You cant start again from where you left off becuase the end was not a concept but a combination of vague concepts and their effects. This means that the only way to think in depth is through uninterruped chains of thought. You can only have uninterrupted chains of thoughts if you have time in solitude and the depth of your thoughts are then limited by the longest uninterruped duration of thinking that you can have. …

Now there is one caveat in solitude allowing the longest chains of thought. Which is that you can keep thinking about vague concepts in vague ways without ever actually turning them into something concrete. And this is where a lot of people get stuck at. After you have spent sufficient time in your thoughts you actually want to try writing your vague thoughts by converting them into words. You are basically trying to think in “type” where instead of interrupting your thoughts to write, you think in writing by just starting to write down your thoughts.

The thread in that screenshot was my after-thought to the difficulty I was having in thinking in type described in the thought-reference. So, I was basically having this tension where I was becoming ever more skeptical of my whole thinking (like, is the panorama even there or am I suffering from a thinking-schizophrenia?) because when I attempted to re-think those thoughts in words, they just wouldn’t come; without that multi-dimensionality there was nowhere to begin from. That was even more problematic because if somehow, I could grasp them in a concrete manner, I could at least shrug them off saying, nah they don’t make any sense, but now I couldn’t even do that, because absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. But also, if there’s no evidence, then on what grounds am I standing on? I can’t live suspended in the air.

Reading Henrik’s essay clarifies a lot of things.

It seems the problem I have is this. What I have called the panorama is sort of a web of associations in a higher dimension space. It feels blurry because the eyes-equivalent-of-brain are physically incapable of looking at it in a distinct manner. What we can look at, is a representation of it that has been compressed into a lower dimension. But compression with minimum amount of loss, is very resource intensive. My brain is low in this processing power, which makes the compressing process computationally slow. Then, the working-memory of my brain is also very limited, and hence the residual accumulation exhausts it before the computation completes. The process crashes.

The way to get anywhere, it seems, is to not to try to compress the whole panorama at once but some chunks of it, that are large enough to contain useful associations. If somehow, I can keep hold of at least two remote points and the association between them2, from the high dimensional space to low dimensional space, I will have something concrete to build further upon. And the good thing is that our hardware is flexible. If we keep exercising these compression computations, our working memory expands and processing speed improves, and thus we can bring in larger and larger chunks from the high dimensional space to the low dimensional one3.

Looking at the writings in my weblog, it seems I have been able to run a handful of computations involving compression of very small chunks of that wider panorama, without crashing. For those of you who have seen me, I feel just as much progressed with this exercise, as I would feel if I went to a gym someday4.

But the thing is, this whole affair is not about compression at all. It’s about building a better model in the higher dimensional space—a model that is closer to truth. That is why we compress it into lower dimensional space, in the first place, so that we can scrutinize it more thoroughly, looking for contradictions and flaws, and fix parts that need to be fixed, and demolish parts that need to be demolished, thus updating the high-dimensional model5. A very useful by-product of it though, is that we can share results of our findings (based upon scrutiny of the compressions) with others and read findings shared by others, and based upon our personal re-inspection of others’ findings, speed up the model-iteration process by magnitudes.

- Probably more often than this, I do the other kind of stroll in which I do think in words—or speech to be precise. It’s a conversation I have with myself. [Probably, that’s why I have become accustomed to circling on the roof my hostel or veranda of my home (where I am alone), instead of something like a park, because I find it very hard to have a deep conversation with someone in presence of others (regardless of whether others are paying any attention or not). Even though I don’t actually speak aloud the words when I am talking to myself, but it shows in my behavior (I laugh at funny things and even slap myself (though much rarely))]. ↩︎

- The other kind of stroll where I talk with myself (or think in speech/words) also helps make new associations, but those are mostly with points much closer in that high-dimensional space. ↩︎

- But, the compressions are still lossy. You can’t substitute them for the thinking in high-dimensional space. Physicists or mathematicians are able to talk to each other in words or symbols, only when they can map the compressed representations to their own individual thinking in the high-dimensional space. ↩︎

- Those who have actually seen me know that’s a false comparison. The state of affairs is much more feeble in meat-space. ↩︎

- If I am not mistaken about the technical processes, this happens with LLMs only in the training phase. Once an LLM model has been trained, it is not re-updating its model with every single computation it does—unlike human beings. ↩︎

-

Demolishing old models

I turned 22 a while ago. Which is an irrelevant fact here, as my writing this is in response to something I read1, and I would have written it even if I hadn’t turned 22.

When I was a bit younger, I used to think that I knew how the world works. I used to think that from much earlier age I guess. But every few years, I would realize, how naïve I have been, and would get disappointed at my younger self for being so. I also used to think, apart from that, that I knew how the world ought to work. While I kept realizing every few years that how I thought how the world worked was so utterly mistaken, I never really realized that I was similarly mistaken about how I thought the world ought to work2. With new things unfolding in front of me as I poked at reality, I demolished things from my mental model of how the world worked that weren’t right and built new things to replace them that better fit reality. But for the other mental model of how the world ought to work, I merely built new things in respect to new things unfolding in front of me and never demolished anything. That model was very precious, and so I plucked out nothing but weeds and shrubs, but I kept building and building, with increasing sophistication, in order to accommodate everything and everyone and to handle all edge cases, the task becoming too complicated and too burdensome, but still failing to meet its purpose. Just like in a bureaucracy or corporation, where to solve a problem, you can’t remove anything, say, from a constitution or a codebase, only add more things. But the problem never gets solved, only evolves into a more complicated form to which you surrender to attempt to solve.

Henrik in an essay wrote how he wanted to have a book that he could give to his 7-year-old that taught her how to handle being sentenced to freedom, borrowing Sartre’s phrase. It is at 22 that I realize with my full consciousness, that I have been sentenced to freedom. As Henrik quotes a character from a Dostoevsky’s novel, we humans long to submit to authority, and so did I, and actually still do, but that doesn’t change the fact. I feel as much frightened as does a 7 year old. But now I have grown old enough to stop seeking comfort in what’s probably not true. Even though I know very little of him, I gamble that truth also has some comfort to give me.

The other model, of how the world ought to work, needed as much demolishing if not much more. But at this point, I will have to dismantle it very carefully. It’s not wise to just blow things apart. Because most of these building blocks are useful and important, and actually their much being useful to me was the very thing that made it harder for me to demolish the building. But I can dismantle it carefully, so that I can discard what I am not sure is right, and preserve what I think is important. Perhaps I don’t need to build something to accommodate everything and everyone. I can start from something small, a home for me.

-

Buying e-reader in Pakistan

When I was buying mine in March 2025, I found that there’s only one guy in Pakistan who imports used or almost-new e-readers from abroad. You’ll probably find the same guy on FB, OLX, Daraz, etc. (with usernames Syed Online Store or Readers are the leaders).

I found that I care about three things most. 1) Screen Size, 2) Frontlight, 3) Display Resolution.

Screen Size

Small screen size means more page turns per book. Almost 80% of ereaders you’ll find would have 6-inch screen. This is equal to some mobile phones, just less rectangular. For book-reading, it felt too small. So, you should try finding one with 7 inch or 8 inch screen. Mine is 8 in, and it is perfect. Larger than 8 inch give more of a magazine feel and are suitable only if you wanna read scientific papers, mangas, PDFs with large paper size, or stuff like that.

Frontlight

Eink readers are supposed to give a paper like feel, but still since there’s a thin plastic touch screen between the display, light is not reflected back from the surface as good as paper itself. So, when you take the e-reader outside, it will be readable perfectly, but in a normal room where you can read paper properly, you will find the e-reader not so well lit unless you are directly sitting under a tube light or something. So, you should opt for an e-reader with frontlight. You will also need it if you wanna read at night with lights off. (The seller will call it backlight, but he means the same thing).

Resolution / Pixel Density

E-ink display technology has evolved a lot between 2010-2020. Older models used E-ink Pearl technology which had around ~167 dpi but newer models with E-ink Carta display have around ~300 dpi (same as book-print quality). For good reading experience, make sure not to buy anything <250 dpi.

Note: Resolution (such as 1448 × 1072) is only comparable if you are comparing same screen sizes. The proper comparison is thus by using pixel density (dpi/ppi). The seller might not know exact resolution/dpi but just tell him you need one with good resolution and google the exact dpi for the models he shows yourself.

Manufacturer / OS

Amazon’s Kindles have largest e-reader market share, but that is mostly because of integrated system with Amazon’s kindle store. But if you are not buying e-books from Amazon kindle store (maybe because *coughs* the author directly sent you an e-book file), standard .epub files won’t run on Kindle. So you either need to

find*coughs* ask the author for AZW3 or MOBI version, or convert the file. Also, Kindle’s overall UX isn’t considered good. Kobo’s UX on the other hand is considered best among all e-readers (based on user reviews).Now Kindles and Kobo both use their own OS, but some e-reader brands like Nook use Android. Android is an overkill if you wanna use e-reader just for reading stuff and hence should be avoided unless specifically needed as it will consume more battery etc.

How I bought mine?

I actually didn’t know all this info. It took me a lot of googling and some experimentation to learn this. I asked the seller to give me a list of all models he has, so that I can choose. When he gave me, I gave that to Grok and prompted it to google relevant specs and it returned a table, which I took to Excel and filtered according to my needs and decided. First, I bought a 6-in Kobo Clara (which had front-light not working1 and thus I could get it at lower price), but realized that 6-in was too small and front-light is necessary. The seller was nice enough to have me replaced it. I then chose an 8-in Kobo Forma (with minor scratches and page-turn buttons not working) which was the only >7-in model he had at that time with good resolution.

How to buy yours?

First check out Ereader ComparisonTables to get an idea of different models and their features and decide what features matter to you.

The seller I mentioned earlier is generally less responsive, due to other workload or something, and so he’ll reply late. If you’re in Karachi better visit his shop, or if you wanna buy online, try to share your requirements clearly early on so that it takes less back and forth for the final decision. It took me around a month from initial inquiry to final decision, which probably is not a good way to do it.

Other options are some shops that import new Kindles, or people who would have bought it from abroad, and are selling their used ones on OLX or FB groups.

After you buy your E-reader

If you are a nerd and need the best reading experience, KOReader is a must. Most e-reader UX’s suck and allow very little customization. KOReader is a third-party open-source software that can run on most e-reader devices (earlier it couldn’t be used on Kindle, but now even Kindle jailbreak has been released). It has some initial setup overhead, but with KOReader, you can make the device fit your needs. Kobo’s UX is best among all default manufacturers but even still, the page turns are slower on Kobo’s default UX (called Nickel) than if I use KOReader on same device. There are some engineering reasons behind it. There’s another third-party software called Plato which is even faster than KOReader but is less customizable.

- Note: The seller would also have some models with some defects, which will allow you to buy them at lower price. ↩︎

-

Institutionalized

Humans have a tendency to get institutionalized. i.e. to get used to a way of things, e.g., prisoners sentenced for life at a young age get institutionalized to life in a prison and when offered parole at a later age, find it painfully difficult to live a life of freedom. This is also the reason old people find it very hard to migrate to a different house, city, or a country.

We not only get institutionalized about our environment, but also our way of seeing things and thinking about things.

One particular pattern of getting institutionalized is when a not-so-good system helps a person escape a terribly-worse system, but then the person gets institutionalized to the not-so-good system. Thus, later when he gets to see way better systems, he cannot wrap his head around the fact that the system that saved him from the terribly-worse system is actually not-so-good, and starts thinking that something must be wrong about these better systems, even if he can’t see anything wrong. In an extreme end, he’ll start making up wrong things about these better systems.

This pattern is very apparent in people that join rebellious groups, for instance, criminal gangs that help someone out of some serious trouble. But rebellious groups are of all sorts, e.g., we had a rogue student-organization in our university, that was a very small ineffective rebellious group1. But then there are also, political factions, cults, etc.

But this pattern is more common in our everyday ways of looking at things or thinking about things.

For instance, one might notice that there are so many people or places that promise to help you achieve x, but later realize that all of these people or places are frauds or are ineffective, he might get skeptical not just of those fraud or ineffective people, but even of the fact that x is something achievable. In some cases, x might actually be unachievable e.g. if someone promises you to bring back the dead. But in everyday cases, x are things that are achievable, e.g. understanding about things, good friends, happiness, etc. So, for instance, if an actually happy person meets such an institutionalized-skeptic of a happy life, he cannot believe that living a happy life is even possible. Similarly, someone who could not understand things by reading textbooks would think that he is incapable of understanding things (most textbooks are extremely poorly written, or in many instances the person lack the pre-requisite knowledge for understanding a concept, where it’s better to re-start learning from first principles).

That was a common person example, but this is a pattern in overall way of institutionalized thinking. For instance, Einstein had gotten institutionalized to his relativity model which was a way better understanding than Newtonian model, but he couldn’t grasp the quantum theory when it came along which provided an even better explanation about some things.

How to de-institutionalize then? For anyone who has had experience helping old people switch to a newer technology will know how hard it is for them to grasp it, even when the newer technology is more convenient. So, before you think about de-institutionalizing, re-think if it’s really necessary. If it involves other people, you should respect their preferences on your own, because you might end up doing them more harm then good by trying to de-institutionalize them.

The only valid question then, is how to get yourself deinstitutionalized. The difficulty of getting out of a bad system is proportional to the time you have spent within. But even still, among people who have lived same time institutionalized, some get deinstitutionalized while others don’t. And it seems the pattern with them is that they interact more with people from other systems. But not just other systems, but better systems. So, they interact more often with people who look at things more perceptively, people who think about things more rigorously, or people who live their lives more fulfilled. But the important thing is that they engage in an honest dialogue and not a debate. Someone who actually has a better system has no need or desire to argue with anyone else. And so if one interacts in a debate-ish way, the people with better systems will start avoiding him, and he will find himself arguing with people who like arguing, which is people with other equally-bad or worse systems. And that is a terrible way to get locked-in in your institutionalized thinking.

- There was a classmate of mine who was an active member of it. He was a nice boy otherwise in class, so I couldn’t understand why he joined that. I tried to avoid bringing up this topic, but as I talked more to him, he started telling about it himself, and I realized what was the thing. He was a shy and cowardly kid, but joining this thing made his cowardice go away, and so he became blind to all the morally wrong things this group was doing, even though he himself had good morals. ↩︎